Another example, although less extreme, of Kipling’s mastery of rhythm, making the complex seem deceptively simple, is his description of the long sea voyage south in ‘L’Envoi’, often known as ‘The Long Trail’.The salt made our oar-handles like shark-skin; our knees were cut to the bone with salt-cracks; our hair was stuck to our foreheads; and our lips cut to the gums; and you whipped us because we could not row. Will you never let us go?

Many of Kipling’s historical poems were written with children in mind and inserted between the chapters of Puck of Pook’s Hill and Rewards and Fairies, or The School History of England, which he wrote with C.R.L. Fletcher. ‘Dane-Geld’ and the much loved ‘Roman Centurion’s Song’, for instance, in which the Centurion, after 40 years’ service in Britain, pleads not to be sent back to Rome:There’s a whisper in the field where the year has shot her yield, And the ricks stand grey to the sun, Singing: ‘Over then, come over, for the bee has quit the clover, And your English Summer’s done.’ You have heard the beat of the off-shore wind, And the thresh of the deep-sea rain: You have heard the song — how long! How long! Pull out on the trail again! Ha’ done with the Tents of Shem, dear lass, We’ve seen the seasons through, And it’s time to turn on the old trail, our own trail, the out trail, Pull out, pull out, on the Long Trail — the trail that is always new!

Kipling’s poems written for children are among his best. He had no need to show off or prove his worldly credentials. All could be kept simple, as in ‘Harp Song of the Dane Women’:For me, this land, that sea, these airs, those folk and fields suffice. What purple Southern pomp can match our changeful Northern skies, Black with December snows unshed or pearled with August haze — The clanging arch of steel grey March, or June’s long-lighted days?

Others which have stood the test of time are ‘The Way Through the Woods’ and the clip-clop of ‘A Smuggler’s Song’:What is a woman that you forsake her, And the hearth-fire and the home-acre, To go with the old grey Widow-maker?

Kipling was not only prolific. He was also wide-ranging in his choice of subject. Much of his verse had its roots in England and its history, but he was also inspired by the music hall in his early poems of army life, like ‘Danny Deever’ and ‘Tommy’, published in Barrack-Room Ballads in 1892. Over 20 years later, he was to become a considerable war poet, although from the unfamiliar angle of a father, rather than a combatant:Five-and-twenty ponies Trotting through the dark — Brandy for the Parson, ’Baccy for the Clerk. Them that asks no questions isn’t told a lie — Watch the wall my darling, while the Gentlemen go by!

His bitterness against the Germans and the British politicians who had failed to heed the warning signals is summed up in ‘The Children’.My son was killed while laughing at some jest. I would I knew What it was, and it might serve me in a time when jests are few.

And, later,They believed us and perished for it. Our statecraft, our learning Delivered them bound to the Pit and alive to the burning.

It was Kipling’s fate to be a prophet without honour in his own country. He at least foresaw the dangers ignored by so many. As early as 1902 in ‘The Dykes’ and as late as 1932 in ‘The Storm Cove’ he warned of disaster to come, in both cases with the image of the inexorable tide flooding men’s feeble and neglected defences. In one of the most vivid of his war poems, ‘Gethsemane’, Kipling imagines himself to be one of the soldiers, rather than an onlooker:To be blanched or gay-painted by fumes — to be cindered by fires — To be senselessly tossed and retossed in stale mutilation From crater to crater. For this we shall take expiation. But who shall return us our children?

Many of Kipling’s poems read well aloud, particularly the long monologues. ‘The Mary Gloster’, the deathbed reminiscences of the rascally old shipowner to his effete and unsatisfactory son.The Garden called Gethsemane It held a pretty lass, But all the time she talked to me I prayed my cup might pass. The officer sat on the chair, The men lay on the grass, And all the time we halted there I prayed my cup might pass. It didn’t pass — it didn’t pass — It didn’t pass from me. I drank it when we met the gas Beyond Gethsemane!

Master at two-and-twenty, and married at twenty-three, Ten thousand men on the pay-roll and forty freighters at sea! Fifty years between ’em, and every year of it fight, And now I’m Sir Anthony Gloster, dying a baronite.

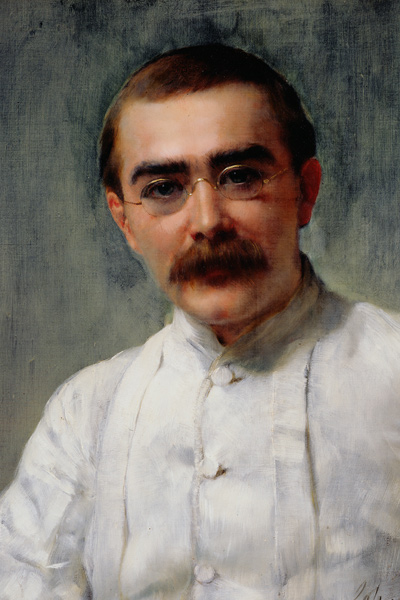

Kipling’s character, with its extraordinary contrast of coarseness and sensitivity, is reflected in his writing

Comments