Sebastian Morello has narrated this article for you to listen to.

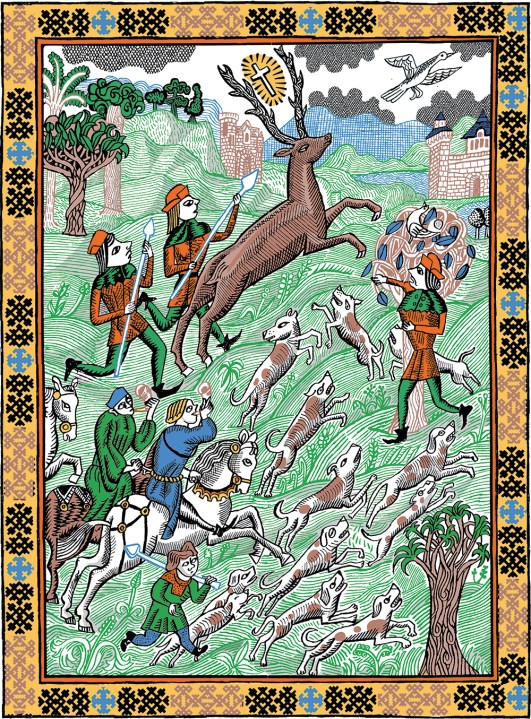

When I was a teenager, my closest friend, Henry, would vanish into the Shropshire Hills over the hunting season’s weekends. When he returned, it was with a wind-beaten face, wearing the traditional beagler’s white breeks and green socks, with a leather hunting whip slung over his shoulder. I knew nothing of this world, until one late autumnal Saturday he invited me to join him. As I watched the beagle pack race across the landscape, I realised I had stepped into a magical event, a hunting scene from a medieval tapestry brought to life. I was hooked.

To this day, many sporting Christians throughout Europe honour St Hubert with songs and prayers after a hunt

Beagling was my entry into field sports, but soon the door might be closed to others. The government is committed to outlawing the pursuit of artificial trails with hounds. This attack on what remains of our hunting heritage stems from bigotry, ignorance and muddled emotion, but it’s also bound up with a rejection of our Christian spiritual heritage, without which modern Britons are finding themselves purposeless.

Henry was the only Roman Catholic I knew growing up. His was an old recusant family and his father was a knight of the Order of Malta. Arriving back exhausted from that day’s hunting, Henry and I collapsed on the sofa in his drawing room. Sitting before the hearth and a roaring fire, under a small wooden crucifix and a glorious painting of the Virgin, we discussed the day’s hunt over hand-rolled cigarettes and homemade damson gin. Two things occurred to me then: that Catholics know how to live beautifully, and that Catholics hunt. Only later did it dawn on me that there is a deep connection – not only historical, but spiritual – between Christianity and the chase.

Christians of old, from kings with royal buckhounds to lurcher-coursing commoners, always hunted. True Christian hunting culture, however, arose in our civilisation with the cult of St Hubert, an 8th-century nobleman and patron saint of sporting Christians. One Good Friday, when Hubert ought to have been in church, he was out on a hunt. Amid the chase, his hounds encircled a stag and kept it at bay, awaiting their master to arrive. As Hubert approached, a cross appeared between the stag’s antlers, and he heard a voice reprimanding him: ‘Hubert, unless you turn to the Lord and live a holy life, you will go into the fires of hell.’ The stag fled, leaving poor Hubert dumbstruck.

Hubert changed his ways and later became a much-revered bishop (and the stag became the mascot of Jägermeister). The Abbey of Saint-Hubert, in what is now Belgium, was renowned throughout Christendom for breeding Europe’s finest scent hounds: the St Hubert hound. These hounds were brought over to England in the Norman invasion and became the forefathers of the foxhound, the harrier, the hunting basset, the bloodhound, the staghound and the beagles used in trail hunting today.

To this day, many sporting Christians throughout Europe honour St Hubert with songs and prayers after a hunt, and there’s even an unofficial Anglican Society of St Hubert for hunting parsons. The most significant inheritance from St Hubert, if the most subtle, is his influence on the Biblical notion of ‘stewardship’.

Stewardship is the belief that we are spiritually and morally beholden to the Earth, which God has entrusted to us for its flourishing. While at first this sounds similar to the sentiment of some of today’s ‘green movements’, which make appeals to moral duty, stewardship sees humanity as an essential part of nature, rather than as an outside force infiltrating nature like a virus.

Take, for example, the misconception that hunting, because it involves killing animals, is therefore cruel, plain and simple. Wildlife management, which often entails the death of animals in one way or another, may indeed be cruel. The challenge is to find a method of killing animals that minimises suffering. Hunting, which provides a way of working with nature rather than against it, aims to do precisely this.

When hunted by hounds, a quarry animal either escapes or is killed. On the other hand, if firearms are the only means to control numbers, injuries and slow deaths are common. Houndwork always stuck to the traditional hunting seasons, avoiding the killing of pregnant vixens. With only firearms to manage numbers, it is now open season all year round. Fox cubs regularly starve to death in dens after their mothers have been shot while out looking for food. Pregnant vixens are often killed.

The red deer of Exmoor are the healthiest in Britain on account of the staghound packs there, which, through careful management, saved the deer from extinction in the 19th century. Staghounds instinctively isolated sick deer, to be dispatched by a rifleman, but now these herds are no longer protected from bovine TB and other infectious diseases.

Charlie Pye-Smith, in his work of investigative journalism entitled Rural Wrongs, demonstrated how crucial hunting in the UK has been to conservation and habitat protection. He established that top-down attacks on hunting have caused ecological disasters, chiefly for the traditional quarry species whose habitats were protected by the hunts.

Perhaps, though, we should be equally concerned about the spiritual disaster wrought by our turn away from stewardship. We’re encouraged to fly from reality and into virtual reality, from actual and settled communities to ‘online communities’, from personal relations to interaction as opinion-blurting internet avatars. Our modern disconnectedness with the earth is alarming, and it’s increasingly difficult to turn back when it means distancing ourselves from obsessive attachments to devices that forever demand attention and keep us hooked on dopamine.

Hunting frees us from the process of what I would call ‘de-incarnation’. It allows us to see the drama of the natural world from within, to enter the realm of other animals and not only to meet them on supermarket shelves where they sit as indistinguishable blobs of dead flesh covered in clingfilm. Through hunting, the world ceases to be ‘the environment’ – stuff with which we’re surrounded and to which we have no essential connection – and it becomes nature, God’s creation of which we ourselves are a part.

Sebastian Morello’s Mysticism, Magic, and Monasteries is out now.

Comments