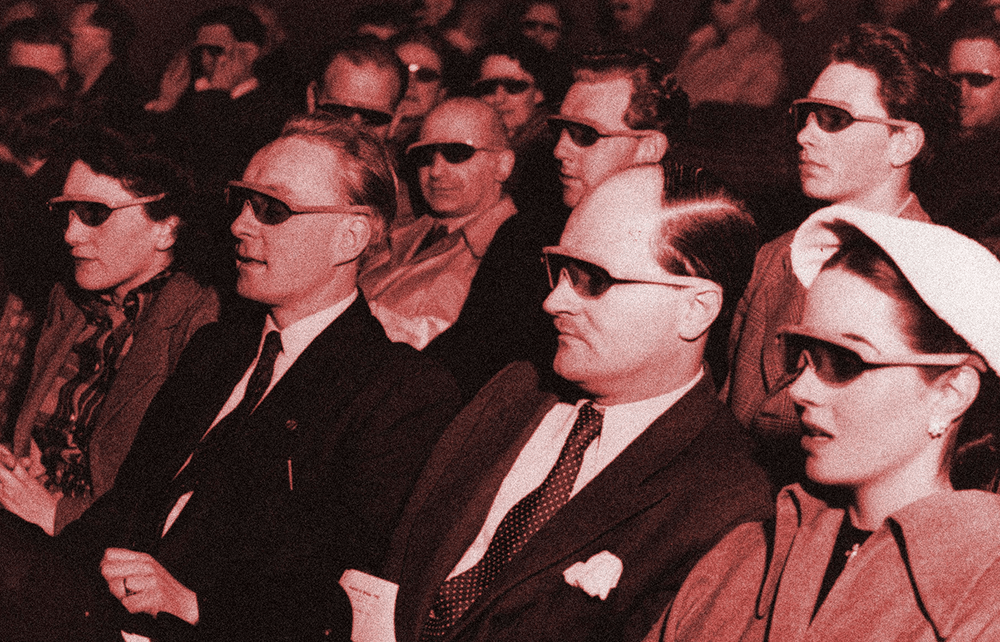

I’ve always loved cinema, but hardly ever cinemas. It’s no surprise to me that movie-going audiences are in decline. Ticket sales this year are only $4.8 billion, down from $6 billion in 2023. Apparently 65 per cent of Americans now prefer to watch a movie at home, compared with 35 per cent who say they prefer to watch it in a theatre. This is probably due to improved home cinema technology and the ever-shortening gap between when a movie is released in cinemas and is available at home. The chain of Curzon cinemas sold this month for a measly £3.9 million.

I can’t say that I find this trend upsetting. I don’t miss feeling my shoes sticking to the carpet, small children emptying popcorn down my neck or discovering that my underpants have become infested with fleas.

My worst experience as a cinema-goer came in 1987, as I attempted to watch Oliver Stone’s Vietnam movie Platoon in the crumbling structure of the Odeon, Holloway Road. The impact of the My Lai massacre was seriously mitigated by hordes of small children running about the auditorium, shouting at each other and brandishing weapons, including at least one knife. The child who menaced me with it looked around ten. It struck me at the time that the events on screen were, if anything, less hazardous than experiencing an Oscar-winning movie in an inner-city cinema.

Another event that jeopardised my love of cinematic entertainment came in an even less salubrious cinema on the Holloway Road, where a mediocre comedy suffered the indignity of having its last two reels reversed by an inattentive projectionist. When a customer on his way out timidly asked for his money back, the girl on the door said: ‘What’s the matter? You saw the whole picture, didn’t ya?’ Yes, but as Eric Morecambe remarked to André Previn, not necessarily in the right order. I notice that the cinema has now closed. I think it’s a fast-food joint, where I imagine you can order dessert before your aperitif.

When I became a film critic, initially for the Sunday Telegraph and later for the Daily Mail, screenings turned out to be a good deal less hazardous. Early on in my career, though, a few critics were liable to over-indulge at lunch, especially Ian Christie of the Daily Express, who played in a jazz band. I remember him sitting down in the subterranean Bijou screening room at 2 p.m., next to Derek Malcolm, the imperious Old Etonian film critic for the Guardian. Derek turned to him, fixed him with a beady eye and drawled: ‘Oh my God! I hope you’re not going to keep me awake with your snoring!’

I don’t miss feeling my shoes sticking to the carpet or small children emptying popcorn down my neck

Celebrity critics could also intrude, with nasty habits reminiscent of real-life cinema audiences. Chris Evans, then one of the hottest names in broadcasting, managed to talk through the entire first half of one movie without anyone daring to reprimand him. I recall Rosie Boycott, who had edited one of the Independent newspapers, using a screening to catch up with her emails and phone messages. When I tapped her on the shoulder and pointed out that her shining phone was in my eyeline, she did not seem amused. Come to think of it, I never did write for the Independent.

The back row of cinemas is a traditional venue for groping and other forms of sexual experimentation. One relief of being a critic was not having to witness other people’s heavy breathing – though one senior critic was prone to asthma attacks – or exchanges of bodily fluids. Of course, as in real-life cinemas, you never quite knew who you were going to sit next to. On one occasion, Kristin Scott Thomas sat down next to me and I found it extremely hard work to keep both eyes on the screen. On the other hand, I remember another screening – at the Curzon, Shaftesbury Avenue – when Michael Gove plonked himself next to me. The film we were viewing was The Lives of Others and I still count it as one of the best movie experiences of my life. I can’t speak for Michael, but I don’t think either of us distracted each other at all.

Alas, spending an excessive part of one’s life in cinemas does little for one’s physical health. After 30 years sitting in darkness, I found myself suddenly racked with muscular pains. My doctor – yes, in those days I actually had one I could call my own – diagnosed me as having ‘burka disease’. He explained that it was Vitamin D deficiency; and he had only experienced it previously in Muslim women who spent their days shrouded in black and thus did not receive enough exposure to sunshine. I’m not sure what happened to that doctor; he’s probably under investigation for hate crimes.

I’m also not sure seeing so many violent movies was that good for one’s mental health either. When I witnessed a real-life murder – in Canonbury, north London – I was disturbed that I had become so desensitised through my job that I wasn’t nearly as upset as the rest of my neighbours.

Covid put the mockers on the whole movie-going experience, especially for those growing longer in the tooth, by rendering visits to the cinema potentially fatal. But long before that, Hollywood’s obsession with superhero movies and with pleasing adolescent Americans to the exclusion of everyone else had whittled away our visits to the cinema to the bare minimum. Back in the second world war, Alan Turing and Joan Clarke bonded over the films they saw weekly at their local Bletchley fleapit, but these would have included masterpieces such as Casablanca and Brief Encounter. They really have stopped making films like that.

Since Covid, friends have taken to coming round to our place and enjoying films on our personal big screen, a legacy of my lifelong love of the movies. Here, we’re able to enjoy the cream of cinematic entertainment, old and new, without being menaced by mobile phones, senseless prattle, fatal illness or ten-year-olds wielding knives. About a month back, we particularly enjoyed a homemade banquet followed by a screening of Babette’s Feast. I reckon that’s called progress.

Chris joins The Spectator’s Edition podcast to discuss further, alongside fellow film critic Tim Robey – what’s their favourite bad movie?

Comments