Very long books appear at intervals about Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. Rarely do they contain anything both significant and new, and they get longer and longer. This one too is a long book, though it is mercifully an abridgement of the original Spanish edition, which ran to over 1,400 pages. Anything in it both significant and new has escaped me. Most of it is about Castro’s childhood, youth, the overthrow of Batista and the early years of the revolution: Castro gave up smoking many years ago, but here he is still puffing away. All the same, it provokes thoughts.

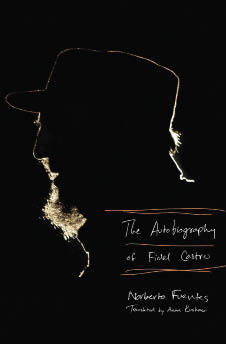

The first is that it confirms the view that history or biography is best written straight, and that funny business should always be avoided. Here Norberto Fuentes takes on himself the task of writing Castro’s memoirs for him, and throughout he writes as Castro. In that he goes a step further than the more sycophantic Ignacio Ramonet, who recently entitled his own interviews with the subject My Life, by Fidel Castro.

Apart from the obvious risk of Castro’s being among other things a tireless and long-winded egotist, not a writer to imitate lightly, this makes his account almost useless for any serious purpose: specialists may find it from time to time suggestive, but despite the author’s assertion that he can back anything up with some source or other, the reader has no means of evaluating the claim.

He was well acquainted with Castro and his entourage, got into trouble and was extracted from Cuba in 1994 through the good offices of Gabriel García Márquez. No vow of silence was obtained. Perhaps — this is a speculation, not an encouragement — his own autobiography might be worth reading, but it is the only one he has a right to write.

The second thought comes from the book’s enormous load of irrelevant and frequently trivial detail, piled on in the hope that it will give the work authenticity: a more educated future era, if any such should ever occur, will surely take this common failing as a mark of our current decadence. Here the detail, combined with the insistent dropping of unmemorable names, is about killings, executions, small-arms and not-so-small arms (no surprise, the author is best known for his Hemingway in Cuba), aeroplanes, cigars and sex — if there is a Bad Sex Prize offered by the Casa de las Américas, he would be a favourite to win it.

Just occasionally the detail is diverting: one admires the enterprise of the Belgian jewellers who fed Trujillo’s mania for fresh medals and orders on their assiduous visits to the Dominican Republic, and who later shared the profits of a Castro drive to get the Cubans to trade in their old gold. Just occasionally, much too rarely, there is a telling observation.

Reading Ramonet led me to ponder the role of boredom in politics — does it maintain regimes, does it eventually overthrow them? — thoughts that certainly recur on reading Fuentes, and which once struck me forcibly when faced with shelf after shelf of the works of Brezhnev in the main Havana bookshop, the unaptly named Casa de Poesía: whatever became of them? I sometimes wonder. Here one is faced again with the power of revolutions to smother the previous or rival cultures of the country concerned, and for their leaders to impose a style of thinking and writing that, however rebarbative, seems after a time to be the natural local mode of expression. One suspects that many outsiders fall into this trap, and here they have concluded that foul-mouthed and insouciant authoritarianism, swaggering machismo and the odd knowing tit-bit of local folklore, Fuentes’s Castro, is somehow the essence of Cuba.

Anglo-Saxon publishers have something to answer for: Americans, one publishing joke goes, will do anything for Latin America except read about it, and this sort of offer will strengthen that resistance. There is still even now more to Cuba than Castro, there is a history of Cuba before the revolution, there are other Cubas of the imagination, there is a Cuban literature which one can turn to for relief. If it’s cigars you want to read about, try the extraordinarily witty Holy Smoke of the late and much lamented Gabriel Cabrera Infante. For a complete change of mood, there is Firbank’s Havana-inspired Prancing Nigger: title apart, I wonder if it was offered today what publisher would have the nerve and independence to take it.

Comments