Unexpected parallels between our age and another are a staple of the jobbing journalist’s trade.

Unexpected parallels between our age and another are a staple of the jobbing journalist’s trade. Usually coinciding with a major exhibition at the Royal Academy, such arguments tend to claim that there are a surprising number of similarities between, say, the Byzantine Empire and the way we live now. Despite the fact that these arguments often result from a brain-storming session round the conference table, there is usually enough there to sustain a page or so. Human nature does not change so much, and some very unexpected idiosyncrasies recur at regular intervals.

Ferdinand Mount has set himself a rather more ambitious task, and his argument is more intricate than usual. He suggests that the characteristic fads of the classical world have, in recent decades, come back to us without our recognising the fact. The Greek and Roman love of pleasure, indulgence, fantasy and opulence are recapitulated in some of the most characteristic statements of our time. Jade Goody, the ‘spa experience’, Cherie Blair’s New Age entourage and Damien Hirst all have their ancient-world originals. There is nothing new under the sun.

Some of the parallels that Mount draws are startlingly close. An ancient foodie like Archestratus, in his snobbery and his geographical precision about where to get the best fish sounds exactly like a modern magazine writer on the subject: ‘When you come to Miletus, get from the Gaeson Marsh a kephalos-type grey mullet and a sea bass . . . that is where they are best.’ The ancient obsession with tales of exotically themed dinners was revived in the 19th century by Grimod de la Reynière’s famous funerary dinner, and J. K. Huysman’s Black Dinner. Such exotic themes at the dinner table continue to this day, courtesy of Heston Blumenthal, who has indeed cooked Roman dinners on television.

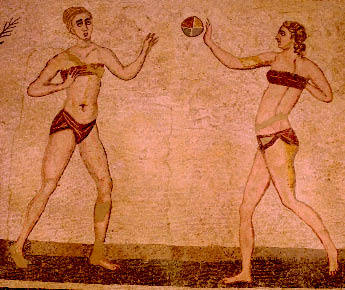

Mount has no trouble in drawing parallels between the immense contemporary ‘spa’ industry, devoted, in its hideous favourite word, to ‘pampering’, and the colossal baths of antiquity. We are at least as fascinated in the fatuous cult of athletic fitness as the ancients, and to much less obvious purpose. Mount casts a beady eye over the principal revivers of physical fitness in the modern age, the militarising Germans, and then wonders what it is all for:

There is little that seems ‘bold’ and ‘merry’ about our obsession with keeping in shape. On the contrary, it seems a somewhat timorous and joyless pastime, a sign of our fear of death rather than of our readiness to confront life.

He ventures, too, into the question of sex, and discovers that the rise, since the 1960s, of casual promiscuity — the ‘zipless fuck’, the expression ‘no strings attached’ — is much more like an aspect of the ancient mindset than we usually suspect. To the question ‘Do you fancy a shag?’

Theocritus or Catullus . . . would have been quite unmoved, and responded simply: ‘Your place or mine?’ For sex is as natural as eating and drinking. Why should anyone think twice about an invitation to a decent restaurant?

Not everything goes quite so convincingly into the parallel:

Just as there is scarcely a remote pueblo or hill village that is unaware of Mick Jagger, so Mithras was a familiar cult figure to soldiers and the local natives in places as far afield as Austria and Slovenia and Caernavon and Hadrian’s Wall.

And other points in his argument are not real parallels, though often amusingly explored. It is true that hardly anybody in the ancient world read silently; when St Augustine habitually did so, it was remarkable enough to be worth commenting on. Interesting as this is, I don’t think it can really be brought into comparison with the late unlamented Labour government’s apparent policy to make public libraries as noisy as possible: ‘Learning is not all about quiet contemplation. I want to see libraries full of life, rather than quiet and sombre. Attractive buildings exuding a sense of joy’, as Andy Burnham put it. He wasn’t talking about reading out loud: he was recommending meaningless yacking.

Nevertheless, some very unexpected comparisons turn out to bear fruit. The multiplicity of spiritual choices in the Roman Empire around the time of the Antonine emperors sounds very modern:

You could believe in anything or nothing. You could put your trust in astrologers, snake-charmers, prophets and diviners and magicians; you could take your pick between half a dozen creation myths and several varieties of resurrection.

In our contemporary, think-for-yourself, spiritual supermarket, heavily influenced by an increasingly multi-cultural mix, pretty well the same is true. Apart from (as far as I know) snake-charmers.

Even the most characteristic phenomenon of our times, the descent of random and undeserved celebrity, has an exact parallel. The Emperor Hadrian met and fell in love with an obscure farmer’s son from Bithynia on the Black Sea, Antinous; when he drowned in the Nile, Hadrian ordered an empire-wide cult of his lover, and thousands of images survive. There was nothing at all remarkable about Antinous, as far as we know, apart from his beauty, but that was enough. Antinous, who became a god, would have perfectly understood the careers of Kate Moss and Jade Goody.

These parallels between the ancient world and ours are intriguing. But perhaps the richest and most suggestive part of the argument comes when Mount addresses what came between; the huge stretch of time separating the ancients from us, when the beliefs and practices of society seem extraordinarily remote from our way of thinking. One of the main claims of this book is that we have become detached from the 1500 years of Christian thinking, and the culture which succeeded the Romans is now much more peculiar to us than they are.

Certainly, the Christian attitudes to sex, to food, to questions of the body such as washing and exercise are now extremely exotic, not to say bizarre. Mount has no trouble at all finding exemplary figures of early Christian times who would now, unlike the heroes of antiquity, be treated as mentally ill. St Anthony ‘boasted that he had never washed his feet in his life,’ and most Christians believed that baptism was the only bath that mattered in their lives. As for sexual expression, ‘an Egyptian monk of the fifth century dipped his cloak into the putrefying flesh of a dead woman so that the smell might banish thought about her.’ Many early thinkers believed, like Augustine, that marital relations were a matter of ‘descending with a certain sadness’ to the act.

All this seems barking mad to us now, and modern-day attempts to reconcile our neo-Pagan practices with Christian culture have their comic side. Mount has discovered some wonderful gym-going Roman Catholics, who

pray while using the rowing machine. ‘At the rate of one word per stroke, rowing one mile on the machine takes me one Our Father and two Hail Marys.’

In a still more unlikely juxtaposition, deconsecrated chapels and churches have been turned into temples to the body cult. At Claybury, in Chigwell, the chapel of a Victorian mental asylum has been turned into a gymnasium and pool, neatly bringing together two very different sites of guilt, penance, reparation and purification.

Inevitably, the argument comes down to regret that, whether you compare us to the ancients or the Christian era, we seem somewhat lacking — the Baths of Caracalla were no doubt rather more of a contribution to civilisation than a suburban spa, and Antinous a more impressive figure than this week’s reality TV star.

Ours is classical-lite, the sensuous, this-worldly way of living without the gravitas th at underpinned it. And without that underpinning, there is something a little flat about it all.

Ferdinand Mount’s ingenious polemic skewers any number of modern-day vanities, and takes us with wit and charm through many absurdities of the remote past.

Comments