The Surreal House

Barbican Art Gallery, until 12 September

Surreal Friends: Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Kati Horna

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, until 12 September

It may not come as a surprise to readers to learn that ‘the individual dwelling [is] a place of mystery and wonder’, yet this is the premise of the Barbican’s latest attempt to pull in the punters. A portmanteau surrealism show that tries to blend art, film and architecture, its reach exceeds its grasp, though the designers must have had great fun carving up the space into dark cabins and voids. Some of the best exhibits — apart from fine things by de Chirico, Magritte and Giacometti — are the films. The documentary made in the apartment of André Breton, Pope of Surrealism, is fascinating, and Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête is a treat, even if Tarkovsky and Godard suffer the torments of the looped; much better than Rebecca Horn’s tired old exploding piano sicking up its guts with the regularity of a cuckoo-clock. Ed Kienholz’s mordant tableau is worth seeing, though when I went the budgie was absent on R&R. You could easily wile away an afternoon here, even if the weighty hardback (£40) accompanying the show is more satisfying than the exhibition.

I much preferred Surreal Friends at Pallant House, Chichester’s flagship of modern art that is always such a pleasure to visit. Nearly all of the temporary exhibition space has been taken over for this triple bill, which focuses on two painters and a photographer who have surrealism and Mexico in common. Apparently visitors tend to polarise between strong partisanship for Leonora Carrington or Remedios Varo (unless they are Surrealist aficionados and find both intriguing), while Kati Horna is virtually unknown in this country and thus a discovery for almost everyone.

This ambitious exhibition begins on the ground floor with a room of Kati Horna’s black and white photographs dealing with ‘The European Years’, before she took refuge in Mexico in 1943. Horna (1912–2000), a photographer of much skill and inventiveness, was Hungarian, Jewish and an active Republican in the Spanish Civil War. She used photomontage to invest her images with the dérèglement of the times. Here are equivalents of Surrealist paintings: the face of a woman emerging over the steps of a Spanish cathedral or a series of evocative shots of Parisian cafés and cut-out figures in the flea-market. Upstairs, there’s another introductory section by Horna, including photos of Carrington and Varo, the collector Edward James and the young John Golding, painter and noted scholar of Cubism, who grew up in Mexico City.

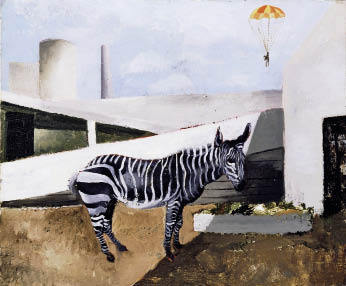

The main room of the new wing is still full of the Pallant House permanent collection, while the satellite galleries around it are playing host to the Surrealists. First come three rooms of Leonora Carrington’s work, obsessional in the intensity of its transformational power, its human shape-shifting. Fabulous beasts mingle with weird figures and there’s an edge of menace to the chill emotional dynamics of these visions, but the gallery-goers seemed to be finding them beautiful and beguiling. Carrington, born in 1917 and the daughter of a Lancashire textile magnate, is the only member of the trio still alive. An artist of tempestuous calm, her imagery (much of it to do with headdresses and the studied gestures of dream) is almost painstakingly hirsute in its detail.

The Spaniard Remedios Varo (1908–63) also paints with an emphasis on the self-consciously frondy, but her work to me looks incurably fey, though her crystalline structures are quite evidently of a high professional attainment. Carrington comes out of the comparison as altogether tougher. Varo’s two rooms contain many wonders of metamorphosis and vegetable growth, but the image I found most powerful is ‘Hibernation’, a small oil of 1942 in which a naked woman in a mosquito net is ligatured to the ground by plants. Above her are ruined towers overcome by vegetation. It’s a sufficiently potent image of sexual deprivation to thrill the most case-hardened Freudian. A final room of Horna’s moving photos, some from a mental hospital and another recording the serried ranks of sugar skulls awaiting the Day of the Dead, complete the show.

A complementary exhibition in the old Queen Anne townhouse where the museum began focuses on Surrealism in Sussex (until 12 September). Edward James (1907–84) lived at nearby West Dean when he wasn’t building a Surrealist folly in the Mexican jungle. Besides being one of Carrington’s greatest patrons he was the friend and collector of other Surrealists, and did much, along with Roland Penrose (who also lived in Sussex), to make surrealism more widely known. This selection of paintings and objects includes such archetypal Dalís as not one but two lobster telephones, and three Mae West’s lips sofas, one in pink satin. There are several interesting Penrose paintings (when will he be given a retrospective?) including a vibrantly coloured portrayal of his wife, Lee Miller, pregnant. And there’s a lovely little Magritte painting of clouds and blue sky typically entitled ‘La Malédiction’.

Back to Surreal Friends, and one notices how many of the finest Carringtons in the first room were owned by Edward James, who collected over 100 of her works, and how filmic the imagery of these painters looks. The handsome catalogue contains essays by Stefan van Raay and Joanna Moorhead among others (£20 in paperback), and the exhibition will travel to the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich (28 September to 12 December). Men dominated the Surrealist group and many of them persisted in treating their women as ‘mere’ muses, rather than as artists in their own right. This exhibition goes some way to redressing the balance. If Carrington comes out head and shoulders above the others, this is no real surprise, but it’s very good to have the chance to see three originals so fruitfully juxtaposed.

Comments