Grammar schools remain one of the most highly-charged issues in domestic politics. There is bound to be controversy about how to boost social mobility and educational standards. But grammar schools bring to the surface other deep undercurrents as well. Were things better in the 1950s? What was Margaret Thatcher’s role in closing so many of them and did she want to see them brought back? Does the call for more grammar schools represent the best of authentic politics shaped by our own experiences, or does evidence-based policy making mean going beyond that? And it is where the Conservative Party fights its own version of class war – those who were privately educated versus those who went to grammar school, while those who were comprehensively-educated look on in bafflement from the sidelines.

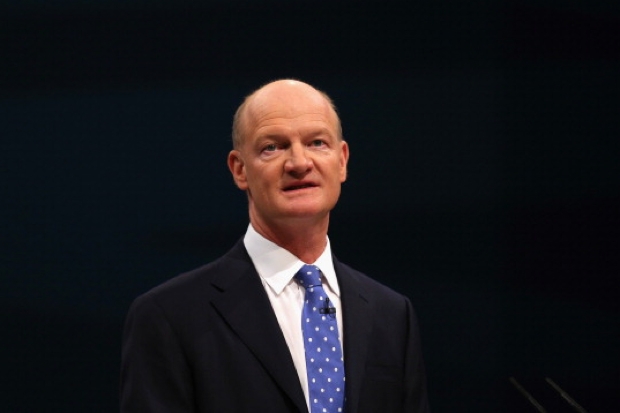

My own experience of this potent mix came with an education speech I delivered on the subject in the spring of 2007. It led to one of the biggest rows of David Cameron’s period in opposition. The current argument brings it all back.

That speech has gone down in folklore as an attack on grammar schools. It is seen as an example of Tory modernisation, breaking with the ‘bring back’ politics which had bedevilled the party during its decade in opposition. And the opponents suspected, just as they did with gay marriage, that the issue was deliberately used by the leadership to redefine the Conservative Party by picking a fight with our own supporters. But what I was really trying to do in the speech was rather different.

The key argument in the speech was that too much of the education policy focussed on who goes where – on the demand side. During the long years of opposition, Conservatives had put our efforts into designing voucher schemes with the aim of delivering school choice, leading us into tricky arguments about whether people should be allowed to pay more on top. This was a zero-sum game: it was about who went where in a static system. My main aim with that speech was to shift the debate to the supply side – how we could make it easier to create new schools which would act as a competitive challenge to existing providers. Otherwise all those promises of more parental choice were pretty empty. As I said in the speech: ‘It is as if we were lovingly focusing on the details of exactly what free railway tickets we should hand out to people without tackling the problem that the trains people want to take are full to bursting already, health and safety regulations make it very hard to add extra carriages and planning rules obstruct the building of new track. It is the failure to open up the supply side which is the reason why, despite years of ambitious attempts at education reform, Britain now lags behind many other advanced western countries.’

I had concluded that years of attempts at education reform had not yielded the results we hoped for because we had failed to make it possible to create new schools. Parental choice would not on its own push up standards unless new schools could be created to meet their demand. This shift in thinking drew on our experience in government with the original precursors of academies, City Technology Colleges. Our biggest single problem had been to find sites where they could be set up, which meant there were far too few of them. I was also influenced by the work of Caroline Hoxby, one of America’s leading education economists. She had studied the effects of new charter schools and had shown that their arrival in an area boosted education standards in all schools, provided that the incumbents could respond to their competitive challenge. Then it really was the rising tide that lifted all boats. But this effect depended on the existing schools being free to respond to match what the charter schools were doing. And nowhere was there any suggestion that these charter schools would achieve their success by selecting their students – it was to be achieved by better teaching methods.

My own education experience played its part too. I had been educated at King Edward’s School, Birmingham, a direct-grant school which was part of a foundation of seven selective schools. Indeed I first got interested in politics when the Labour party in the 1970s attacked selection and direct grant schools – forcing it to go independent or otherwise lose its power to select students. But it was another feature of King Edward’s which particularly set me thinking. The school was one of those marvellous Reformation foundations of King Edward VI. But what made it special was what had happened during Birmingham’s boom years in the 19th century. As the city grew the school could have become ever more socially selective, as had happened to the great medieval charitable foundations like Eton and Winchester. But instead Birmingham’s city fathers recognised that the city needed more schools like King Edward’s and the Foundation grew with the city, ending up with seven schools – one of which was attended by Nick Timothy, Theresa May’s chief of staff.

This is what led me to try to shift policy away from another assumption which dogged Tory thinking – a sentimental, cottage-industry picture of public services. The idea had been that each school should have more and more freedom to run itself and become independent of everyone else. But this was not a very effective way of spreading good practice. It avoided the tricky issue of defining where autonomy mattered and where it was much better to share services. I wanted to see successful schools growing into education chains. We would not win the battle for education reform just one school at a time – it needed to be possible to create new chains of schools, like the King Edward’s Foundation, that would be alternatives to local education authorities

How was this competitive challenge to work? If new schools were to be created to meet parental demand why not grammar schools? It is an obvious and understandable question which arises as soon as you propose opening up the creation of new schools: we could not avoid it. My argument was that if these new schools were able to select their students that would paradoxically make them less effective as a challenge to the incumbent conventional schools. They would simply be able to say that the newcomers were only doing better because they had been able to select the student who would perform best. This remains the crucial challenge to grammar schools to this day – do they really add value or just get good results by selecting the students who are going to do well anyway?

Milton Friedman was very interested in education reform. American free marketeers were powerful advocates of charter schools, but they were not interested in academic selection for them. Indeed if anything they were interested in exactly the opposite model – school admission by lotteries. Their logic was that this was how to put maximum pressure on producers to perform: they should not be able to make life easier for themselves by choosing who they educate. The producers should not be able chose their customers.

So my speech was an attempt to push my party to focus on supply side reform of public services. Michael Gove picked up this agenda and implemented it with vigour. CTCs, academies and now free schools show it is possible for a school with a wide ability range to be very successful. The transformation of school standards in London is an example of what can be achieved. But their critics are always trying to argue that their success is not real, it is only achieved because of who they admit. Theresa May and her advisers are clearly aware that grammar schools are open to this critique and are setting new and ambitious conditions which they hope will ensure they are more representative than are at present. They ask who can object to a bit more diversity of provision. The question is what this means if you are running an academy in a tough area which aims to educate well across the ability range and across a range of social backgrounds. If a grammar school opens up nearby will that model of academy schools still be viable? This is a challenge which the advocates of grammar schools must address because it is crucial that the reforms set out this week do not break with one of the most effective public service reforms we have seen in decades.

David Willetts is Executive Chair of the Resolution Foundation

Comments