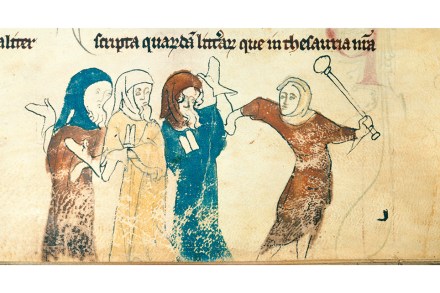

Alchemy – the ultimate fool’s errand

Alchemy, astrology and medicine (before the triumph of germ theory): three worthless intellectual systems which provided a good living for many into the 18th century and even beyond. Alchemy turned into chemistry; astrology was divorced by astronomy; and medicine (which might have become Pasteurism or Listerism) somehow kept its old name while abandoning all its old therapies. There have always been people with the good sense to say that alchemists and astrologers were charlatans, and doctors were more likely to kill you than cure you, but few listened. After all, all three could claim to be ancient, respectable forms of learning. And all three were too good to be true.