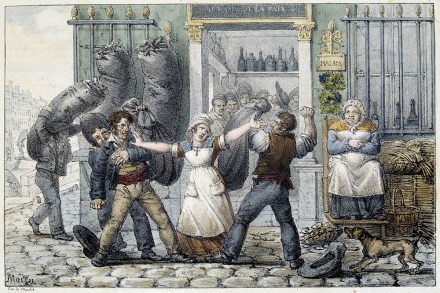

Eat your way round Paris

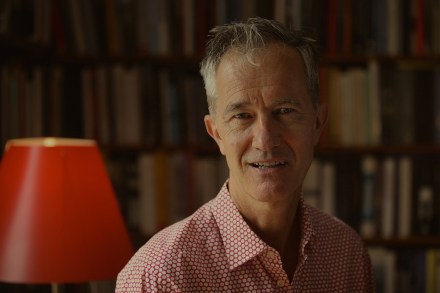

‘Paris, like many old cities, is saturated with blood.’ The food writer Chris Newens certainly knows how to draw the reader in. A Londoner who has lived in Paris for the past ten years, he sets out to eat his way through all the arrondissements, starting with the 20th and spiralling backwards through the coil of the capital. Each chapter evokes the history and atmosphere of a different neighbourhood and focuses on one dish, which the author then attempts to cook in his authentically cramped Parisian kitchen. Newens, who read anthropology at the LSE, comes from a family that ran a bakery and tearoom for six generations and had their