Is it possible to retain one’s dignity in the face of annihilation?

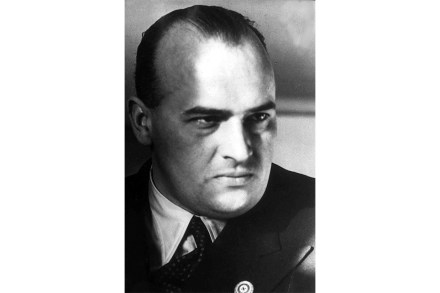

Before the second world war, the Croydon-born cricketer C.B. Fry was offered the throne of Albania. It’s not certain why. Possibly because his splendid party piece involved leaping from a stationary position backwards on to a mantelpiece. Or because, historically, the Balkan nation has been so inexplicably Anglophile as to appreciate the pratfalling funnyman Norman Wisdom. Sadly Fry declined the role and it was later taken by the fabulously named if catastrophic ruler King Zog (real name Ahmed Muhtar Zogolli). Had Fry accepted, history, that capricious monster mixed of chance and fate, would have been very different. In reality, Zog was toppled in 1939 by Mussolini’s invading fascists, who turned